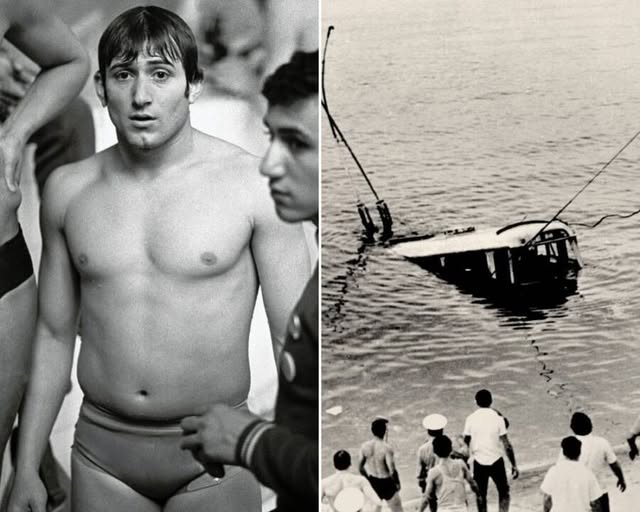

Ninety-two people were on the trolleybus when it plunged into Yerevan Lake. Karapetyan can be seen standing shirtless on the shore.

“It was scary at first,” Karapetyan recalled. “It was so loud, as if a bomb went off.”

“The most difficult thing was to knock out the rear window of the trolleybus,” Karapetyan said in 1982. The broken glass had sliced his leg. “The pain was unbearable… but then I did not think about it — I understood that there was little time.”

He dove again and again, 40 times, bringing up as many people as he could. After handing them off to his brother, who was also a champion swimmer and stayed on the surface to ferry people to shore, Karapetyan went back underwater.

“I didn’t see the person who saved me because he held me from behind when he dragged me up,” one 17-year-old survivor said. “But I remember his hand well — a strong, muscular hand. I could feel I was being pulled somewhere, and then I blacked out again.”

Shavarsh Karapetyan dove until rescue workers begged him to stop. He dove until he emerged with only a cushion and realized that he had begun growing faint from the lack of oxygen.

“I had nightmares about that cushion for a long time,” Karapetyan said. “I could have saved someone else’s life.”

In the end, he pulled 37 people out of the lake, 20 of whom survived. Nine others escaped on their own through the broken window.

Karapetyan bandaged the lacerations on his leg and went home. But that evening, his temperature spiked, and he began to have convulsions. A physician and family friend took him to the hospital, where he spent several heartstopping days in critical care.

The cold, polluted water and wounds on his legs had led to pneumonia and blood poisoning. Though he survived, it seemed all but sure that his athletic career was over. It was three weeks before he was able to walk again.

“Immediately after the accident, some people wanted to publish an article in a newspaper, but this was not allowed,” Karapetyan explained. “In the USSR, trolleybuses were not supposed to fall into the water.”

How Shavarsh Karapetyan Became A Delayed Hero

Following the trolleybus accident, Shavarsh Karapetyan tried to return to finswimming. But his repeated dives in Yerevan Lake had permanently damaged his respiratory system. And he felt a strange, new aversion to being in the water.

“It wasn’t that I was scared of the water,” he said. “I just hated it.”

Brothers Kamo Karapetyan (left), Shavarsh Karapetyan (third from left), and Anatoly Karapetyan (right) wear their swimming medals while posing with a friend and Kamo’s son, Karo.

Nevertheless, he competed a handful more times. Karapetyan set a world record in the 400-meter event at the USSR championship and later won gold and bronze medals at the European championship in Hungary. After that, Karapetyan hung up his fins for good.

He retired at the age of 24, having set 11 world records. Karapetyan held 17 world championship titles, 13 European championship titles, and seven Soviet championship titles.

Like that, Shavarsh Karapetyan became a hero. Soviet authorities awarded him the Order of the Badge of Honor, the Minor Planet Committee named an asteroid after him, and tens of thousands of Soviet citizens wrote him admiring letters.

Karapetyan could have rested on his laurels at that point. But in 1985, when Yerevan’s Sports and Concert Complex caught fire, he raced into the flames to save people — just as he had dove into the lake.

Continue reading…